The Invention of Pairing

I invented code review and pair programming in one day. There, I said it. Who believes me?

Origin Story

The year is 1994 or 1995 and I was working in Rogers, Arkansas with a company called "Delta". It was pretty early in my software development career, and I was a self-taught programmer. My mentor at that company was a veteran called Rick who looked very much like the photos you see of the elder Mark Twain.

Rick and his team of seasoned, professional C and C++ developers were deep into manufacturing process control and working with some of the big food manufacturers on automated packaging and wrapping machines.

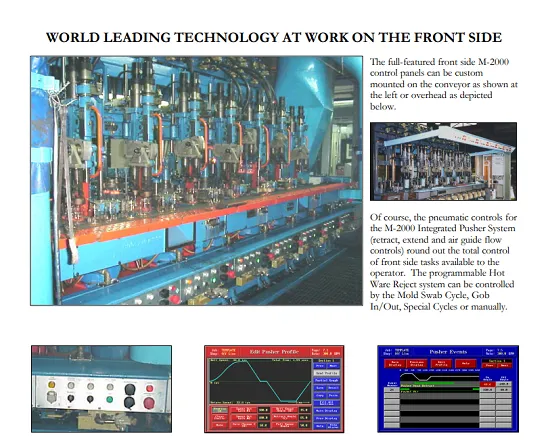

The new projects was to provide a complete automated system to retrofit mechanical glass-forming machines and provide central control over a whole factory-worth of machines from a single management machine but also provide at-machine control devices with touch screens for finer, operator controlled adjustments.

This system used stepper and servo motors, sensors, digital IO and lots of PCs to create a system which replaced the "legacy" clock-work system of actuators and mechanical timing drums with a "modern" UI and finer adjustment capability over timing.

Glass is the Word

Timing is the thing that the whole glass forming machine is based on. The typical glass factory is built around a central furnace which sits high up in the factory roof and heats glass to a horrifically high temperature, delivering it to each machine on a gravity-feed system. Hot glass falls out of the furnace and is cut into a "gob" by a giant pair of scissors. The gob then falls into a iron drain pipe which directs the glass to parallel stations on the machine in a round-robin system. Each station works slightly offset in time to every other one but performs exactly the same operation. A mould is open initially, the glass gob falls into it, the mould is closed immediately and pressurised air is forced into the mould to push the hot glass into the mould and form the specific glassware. The mould is held closed for a few seconds then opens and a mechanical arm lifts the new glassware out of the mould and places it at the front of the machine. Finally, another mechanical arm, called a pusher, pushes the glass out from the machine onto a conveyor belt which takes the glass for cooling and further treatment.

As you can imagine, this is a noisy, dangerous process and relies heavily on microscopic timing (and therefore accurate control) and patience to get one section of a machine working correctly. Now do that for 10, 12, 20 sections in parallel and make them all fit together so that bottles come out of the machine onto the conveyor belt without crashing into one another.

This is one of those situations where we want to be assured that we are correct in our software changes before we go live on the factory floor with super-heated, fast-moving, fragile, breakable, sharp, glass.

Unfortunately that wasn't the way. The team were a bunch of capable, brilliant programmers but very much steeped in the what I now think of as the old way of thinking about developing software. One person per task and build the code on your own machine, ship it and see what happens.

Coding USA

Now one of the first test sites we went to was a factory in Hillboro, Illinois (now closed). The factory was a big, dirty, noisy, open-ended shed which wasn't suited to thinking and algorithmic correctness. So we set up home in a small out of the way shack in the factory grounds but quite a way away from the factory proper.

The first we knew of problems tended to be after someone had done a new build, pushed it live and then went to see how that worked! There's often a big difference between getting code to compile and it having it work as you intend it. This was one of those occasions. You can imagine the scene if they didn't do it completely perfectly. All that split-second timing gone and replaced by a massive pile of cooling, broken glass which the operator on duty had to clear up. Moving cold broken glass is a hazardous thing to do never mind glass that is several hundred degrees that has welded itself around pieces of machinery.

Code Review

Once we had done this over several days and had a pile up several times a day, the operators and management were not very happy with us bunch of cowboy programmers. It's then when I, ashamed to show my face in the factory any more, insisted, with all of the fervour of a young person, that we had to do something. Remember I was ignorant of XP (which was getting going about that time) and the general literature and practices of other developer teams so I'm not sure how I came up with the idea, or even why the other developers let me bully them into doing it. Anyway ... first we tried a process where someone would write their code independently as they had done before but would get someone else to look at a printed out copy of the code with fresh eyes, try to find all the problems with it, send it back for corrections and only push it live when everyone was happy. That helped the numbers of crashes decrease from around 6 per day to about 3. So really good going but still not enough to stop the big hairy, violent looking operators from wanting to murder us.

Pair Programming

So I had another brilliant idea, what about if we shortened that feedback cycle to remove the printing and marking up code and so the idea of pair programming was born. We as a team made a rule that nobody was allowed to write code unless someone else was sitting with them to check what they were typing, discuss and vet what went into production. Suddenly we went from that improved 3 per day failure to one or two a week.

Given that those old mechanical machines used to break down and pour glass on themselves at least once a day, this was a big improvement and I attribute it to changing our working practices to be more collaborative and with shorter feedback cycles.

Extreme?

Now, you might say that a glass factory is a pretty extreme (no pun intended) setting for software development and maybe it is but the lessons from that time have stayed with me throughout the rest of my career and served me well in lots of other industries where the customer cares about their software working correctly just as much as the glass factory did. If the customer sees your software as valuable enough to use it to help them solve a problem, then it's valuable enough to do everything we reasonably can to make sure we get it right.